Clinical reasoning. The first few words you learn as a starting Physio student. It is probably the most important part of our job, but are we doing it well? Among other things, I think this topic is on paper very logical. However when I was a starting Physio, i felt that many times the clear cut clinical reasoning learned in physiotherapy school did not match the reality.

I think a lot of important things we do as a physio are not taught during the education period. In the future I plan to write more about these topics. First stop is clinical reasoning, let’s dive right in.

So what is clinical reasoning? According to the website physiopedia clinical reasoning is:

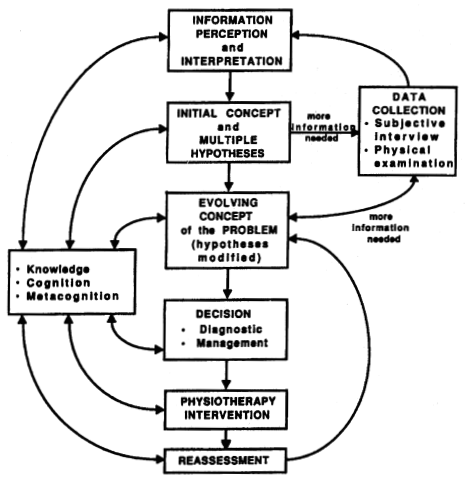

Clinical Reasoning is the process by which a therapist interacts with a patient, collecting information, generating and testing hypotheses, and determining optimal diagnosis and treatment based on the information obtained. It has been defined as “an inferential process used by practitioners to collect and evaluate data and to make judgments about the diagnosis and management of patient problems”

So, I don’t know about you, but when I read this and see figure 1, I think yes I understand that on paper. However I am not sure how this works in my day to day job. Let’s zoom in a bit.

Start at the beginning:

It starts as soon as you see your patient for the first time. You see them limp a bit, or when you reach out with your hand, the want to shake yours with their left. These signs tell you something and already by the way they walk or move your head should get a possible things that might be wrong. At this point you don’t have to be spot on, but it starts. You hypothesize what the problem might be. At this point this still can be anything, so you have a lot of hypothesis.

Patient history:

When the patient sits down and you have gathered all the administrative necessities, we ask what we can do for them. In many cases this is the most important part, because we gather a lot of information during this conversation. We can cross things off our list of hypothesis. If there was no trauma we are likely to cross of the hypothesis that needed an traumatic event to occur. Broken bones are not very likely when the patient did not fall down or there was no impact. Of course there are pathologies that can cause broken bones from the slightest movement, but these conditions are rare. The idea is that we cross of the unlikely hypothesis. I always remember this great quote from a former teacher of mine:

When we cross the street, we look to our right, then left, then right again and we cross the street. We don’t look up, while there might be a plain that crashes down.

While we always keep the unlikely hypothesis in the back of our head, for now we try to cross them off. Sometimes we can ask a simple question, just to be sure. We need to do this especially when the consequences are sinister. That is why we have red flags.

Pattern recognition

When we take patient history, the most important part is pattern recognition. Especially with traumatic injuries. If you listen carefully the patient tells you exactly what happened and what is wrong. If you have the right amount of experience, you might see a light bulb next to you and think; I have heard this before. Don’t neglect this, our instinct is doing very well, but do not go blindly on this feeling either.

The theory is, that if you are starting as a Physio, you have more hypothesis than an experienced Physio. Still both should have multiple hypothesis. So what is next?

Testing the hypothesis

When we have narrowed it down to as few hypothesis as possible, we want to test these hypothesis with our physical exam. When you are a starting Physio, you probably are doing the general movement assessments, the range of motion tests and the “special tests”. This is partly because you still have a lot of hypothesis, but also because you are not quite sure in what to test. Be very careful to be like me as a starting physiotherapist and just do them all.

You should always ask yourself, what am I testing, and why am I testing. More importantly what does the outcome of this test tell me? If it is positive or negative can I cross of one of my hypothesis or better yet do I now have only one or two left?

Remember specificity and sensitivity? Unfortunately not a single test scores 100 on both, but more about that in a later blog.

Diagnosis:

So we have a final diagnosis? It is very likely we have a strong suspicion, but as a physical therapist we do not make a medical diagnosis. We asses the limitations in function, impairments in movement and restriction in participation. We do not give the diagnosis of a pathology.

Photo by Mathew Schwartz on Unsplash

However, we have a suspicion of a pathology. Let’s say our patient comes in with a painful knee and says it feels unstable. He played soccer and when coming down from a header, his knee gave in and he fell. He and other teammates heard a loud “pop”. Our clinical reasoning might give us a few hypothesis like, ACL rupture, MCL rupture, patella dislocation, meniscus damage, cartilage damage. We can test for most of these things and we should, but our main goal is to rule out inner articular damage. If this is not the case, we should refer the patient to a orthopedic surgeon. They have an MRI to confirm the suspicion of an ACL tear, or meniscus injury and this Is why they make a medical diagnosis.

Treatment:

So the first reason we do not make medical diagnosis is simply because we can’t. Although we might have a very strong suspicion of a serious pathology, it is the job of the general physician or orthopedic surgeon to confirm this suspicion.

The second reason is that we as a physiotherapist do not treat pathology, we treat the impairments or limitations of the patient. If our patient has indeed has a torn ACL, he or she might have chosen not to opt for reconstructive surgery. We treat the patients lack of stability, strength, propriocepsis etc. These are a logical consequences of a torn ACL right? Not really. Not everybody with a torn ACL experience lack of stability. So we might only treat the strength deficit, or in the beginning the lack of range of motion. The ACL on its own we might have no effect on at all, since it’s function is not there anymore. Therefor we treat the patient, not the pathology, not the scan (outcomes of an MRI).

Now of course you should study all the pathologies you deal with, because it is important to recognize them and each pathology have their own physical limitations and impairments. It is important to know in some cases what we as a physiotherapist are able to treat or when other specialist are needed to improve the outcome.